⏳ 5 min

What better way to start a PhD focused on PET brain imaging than by attending a school entirely dedicated to MRI?

If you’re a beginner like me, you might find some useful insights in these lines; if you’re a more experienced researcher, perhaps you’ll rediscover — through my words — a bit of the enthusiasm that accompanies the first steps into the world of research.

I would be lying if I said I understood everything at the Erice School (International School on Magnetic Resonance and Brain Function, October 24–29, 2025). Four intense days, filled with talks delivered by the “big names” in the field. After a first day of total disorientation — during which I asked myself more than once, “Benedetta, what have you gotten yourself into?” — I began to realise that the school was an enormous opportunity. A chance to pause and reflect on what my goals are at the beginning of this new three-year professional journey.

Knowing well, but also communicating well

One thing I learned is that doing research doesn’t just mean knowing how to do, but also knowing how to communicate. Listening to so many presentations per day helped me observe the speakers’ communication styles, understand what works and what doesn’t, and develop an initial critical sense of how to convey a complex message clearly.

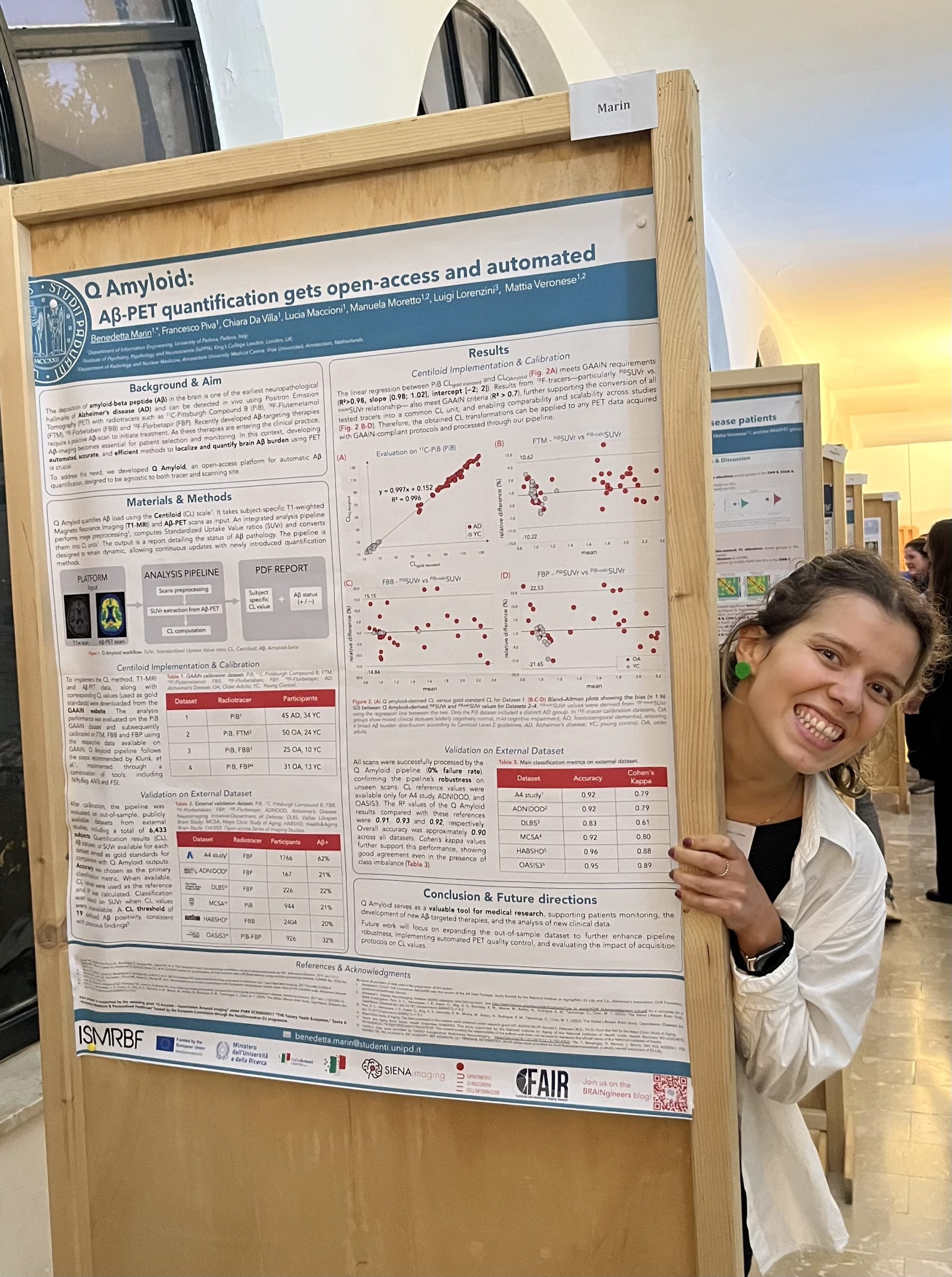

Public speaking is still a challenge — the sweating and anxiety never fail — but it’s an integral part of putting yourself out there as a researcher. After just two minutes of a “flash talk” to present my work, it became clear to me that I still have a long way to go.

Another skill I want to develop (even though it may sound trivial) is the ability to extract the general meaning of a complex talk. I tend to focus on details, and sometimes I miss an entire presentation just because I didn’t understand an acronym mentioned at the beginning. Research is full of technicalities, and it’s impossible to know everything: learning to grasp the structure, the logical thread, the essence of what you’re hearing is a valuable skill. Even when studying a disease like Alzheimer’s, the first question should be: “What is the model behind the pathology?” rather than “What is the microscopic structure of the beta-amyloid that accumulates in the brain?”

Useful, not just interesting research

Another important lesson I’m taking home is the question: “Is what I’m doing actually useful?” True research is born from good questions; otherwise, it risks becoming pure speculation.

My goal is to be useful — and what better way than by responding to a real clinical need? Ultra-high-resolution images, vasculature details and geometry, MRI fingerprinting: all fascinating, of course. But what is it for, in practice? That’s the question I want to keep asking myself.

The most valuable lessons? Around the table

The most enlightening conversations didn’t always happen in the auditorium. During lunches and networking moments, I learned a great deal by listening to informal stories and reflections.

Here are some thought-provoking takeaways:

- Even the most experienced PIs — those we young researchers imagine in our “dream positions” — have behind them winding paths full of choices, attempts, and above all mistakes. As Jorge told me: “If you don’t make mistakes, you don’t learn.”

- We have more and more data, but it’s not enough. Over lunch with Joana, we talked about how we already have a huge number of scanners and an enormous amount of datasets: the market is saturated. What we really need are better methods, new types of integration, more effective ways to analyse, combine, and interpret these data, drawing ever more value from what already exists.

Why study the brain?

Because it’s complex, and we—as humans—are naturally attracted by complexity. The final talk by Andrea Luppi, a researcher with a philosophy background but a PhD in Neuroscience, struck me deeply. He managed to weave thought and scientific rigour together in a clear, concrete, and compelling way. He shared the reason behind his passion for the mysteries of the brain: uncovering what lies behind human consciousness and searching for its signature in the brain’s structure. To answer this question, he studies how patterns of brain activity change across different mental states, perturbed or not: when we are awake, asleep, under anaesthesia, or recovering from brain injury.

And in carrying out these studies — unsurprisingly — there is not only abstraction, but also a lot of mathematics. One of his works, for example, used the decomposition of brain activity into harmonic modes to show how consciousness depends on interactions between the brain’s structure and function.

He showed that under anaesthesia or after brain injury, unconsciousness increases the extent to which brain activity is constrained by its structure — in other words, the brain becomes more predictable and less flexible. This signature can even help identify patients who might still be conscious despite not showing outward signs.

Conversely, psychedelic drugs such as LSD and ketamine seem to break this constraint between structure and function, which is consistent with both physiological findings and subjective reports of altered conscious experiences.

This talk reminded me that the most original ideas often arise from the contamination between different disciplines, approaches, and perspectives.

Dear readers, this post is also a reminder to myself of what I want to learn: let’s see whether, step by step, the lessons from this experience will truly become part of my PhD journey.

• • •

Ho iniziato un PhD sulla PET con una scuola sull’MRI

Quale miglior modo per iniziare un PhD incentrato sull’imaging PET del cervello, se non partecipando a una scuola interamente dedicata all’MRI?

Se sei alle prime armi come me, forse troverai in queste righe qualche spunto utile; se, invece, sei un ricercatore più esperto, magari potresti riscoprire — attraverso le mie parole — un po’ di quell’entusiasmo che accompagna i primi passi nel mondo della ricerca.

Sarei bugiarda se dicessi di aver capito tutto alla Scuola di Erice (International School on Magnetic Resonance and Brain Function, 24–29 ottobre 2025). Quattro giorni intensi, costellati di talk tenuti dai “big” del settore. Dopo un primo giorno di totale spaesamento — durante il quale mi sono chiesta più volte: “Benedetta, ma chi te l’ha fatto fare?” — ho iniziato a rendermi conto che quella scuola era un’enorme opportunità. Un’occasione per fermarmi e riflettere su quali siano, per me, gli obiettivi all’inizio di questo nuovo percorso lavorativo di tre anni.

Saper Fare, ma anche far sapere

Una cosa che ho imparato è che fare ricerca non significa solo saper fare, ma anche far sapere. Ascoltare così tante presentazioni mi ha aiutato a osservare lo stile comunicativo degli speaker, a capire cosa funziona e cosa no, e a sviluppare un primo senso critico su come trasmettere un messaggio complesso in modo chiaro.

Il public speaking rimane una sfida — il sudore e l’agitazione non mancano mai — ma è parte integrante del mettersi in gioco come ricercatore. Dopo appena due minuti di “discorso-flash” per presentare il mio lavoro, mi è stato chiaro che ho ancora molta strada da fare.

Un’altra abilità che voglio coltivare (anche se può sembrare banale) è quella di saper astrarre il senso generale di un discorso complesso. Tendo a concentrarmi sui dettagli, e a volte mi perdo un’intera presentazione solo perché non ho capito un acronimo detto all’inizio. La ricerca è piena di tecnicismi, ed è impossibile sapere tutto: imparare a cogliere la struttura, il filo logico, l’essenza di ciò che si ascolta è una competenza preziosa. Anche nello studio di una malattia come l’Alzheimer, la prima domanda dovrebbe essere: “Qual è il modello che sta dietro alla patologia?”, più che “Qual è la struttura della beta-amiloide che si accumula nel cervello?”.

Ricerca utile, non solo interessante.

Un altro insegnamento importante che mi porto a casa è la domanda: “Ciò che sto facendo è davvero utile?”. La vera ricerca nasce da buone domande; altrimenti rischia di diventare pura speculazione.

Il mio obiettivo è rendermi utile, e quale modo migliore, se non rispondendo a un bisogno clinico reale? Le immagini ad altissima risoluzione, i dettagli dei vasi sanguigni, l’MRI fingerprinting: tutto affascinante, certo. Ma a cosa serve, in pratica? Questa è la domanda che voglio continuare a pormi.

Le lezioni più preziose? A tavola

Le conversazioni più illuminanti non sono sempre avvenute in auditorium. Durante i pranzi e i momenti di networking ho imparato moltissimo, ascoltando storie e riflessioni informali.

Ecco alcune provocazioni che porto con me:

- Anche i PI più esperti — quelli che noi giovani immaginiamo in posizioni “da sogno” — hanno alle spalle percorsi tortuosi, pieni di scelte, tentativi e soprattutto errori. Come mi ha detto Jorge: “Se non sbagli, non impari.”

- Abbiamo sempre più dati, ma non basta. A pranzo con Joana abbiamo parlato del fatto che abbiamo già tantissimi scanner e un numero enorme di dataset: il mercato è saturo. Ciò di cui abbiamo davvero bisogno sono metodi migliori, integrazioni nuove, modi più efficaci di analizzare, integrare e interpretare questi dati, ricavando sempre più valore da ciò che già c’è.

Perché studiare il cervello?

Perché è complesso — e noi esseri umani siamo naturalmente attratti dalla complessità.

Il talk finale di Andrea Luppi, un ricercatore con un background filosofico ma un Dottorato in Neuroscienze, mi ha colpita profondamente. È riuscito a intrecciare pensiero e rigore scientifico in modo chiaro, concreto e affascinante. Ha condiviso il motivo alla base della sua passione per i misteri del cervello: svelare cosa si nasconde dietro la coscienza umana e ricercarne la firma nella struttura cerebrale. Per rispondere a questa domanda, lui studia come i pattern di attività cerebrale cambino nei diversi stati mentali, perturbati e non: quando siamo svegli, addormentati, sotto anestesia o mentre recuperiamo da un trauma cerebrale.

E nella realizzazione di questi studi — non sorprendentemente — non c’è solo astrazione, ma anche tanta matematica. Uno dei suoi lavori, ad esempio, ha utilizzato la decomposizione dell’attività cerebrale in harmonic modes per mostrare come la coscienza dipenda dalle interazioni tra la struttura e la funzionalità del cervello.

Ha mostrato che sotto anestesia o dopo un danno cerebrale l’inconscienza aumenta la dipendenza dell’attività cerebrale dalla struttura anatomica: in altre parole il cervello diventa più prevedibile e meno flessibile. Questa firma potrebbe aiutare a identificare pazienti che potrebbero essere ancora coscienti, pur senza mostrare segni esteriori. Al contrario, psichedelici come LSD e chetamina sembrano rompere questo vincolo tra funzionalità e struttura, il che coerente con i riscontri fisiologici e soggettivi delle esperienze di coscienza alterata.

Questo talk mi ha ricordato che le idee più originali spesso nascono dalla contaminazione tra discipline, approcci e prospettive diverse.

Cari lettori, questo post è anche un promemoria per me stessa di ciò che voglio imparare: vediamo se, passo dopo passo, le lezioni di questa esperienza diventeranno davvero parte del mio percorso di dottorato.

Leave a Reply